There are a variety of tick species here in Pennsylvania. Learning about the different types – including what they look like, where they can be found and what times of year they are active – can assist in protecting you, your family and your pets from an encounter. Here, we will talk about the three most common types of ticks: the Blacklegged Tick, the American Dog Tick and the Lone Star Tick.

The Blacklegged Tick (Ixodes scapularis)

The Blacklegged Tick, also commonly known as a Deer Tick, is an external parasite which gets its nutrients from animal blood and can carry tick-borne diseases including Anaplasmosis, Babesiosis, Bartonellosis, Borrelia miyamotoi (a tickborne relapsing-like fever) and Lyme disease.

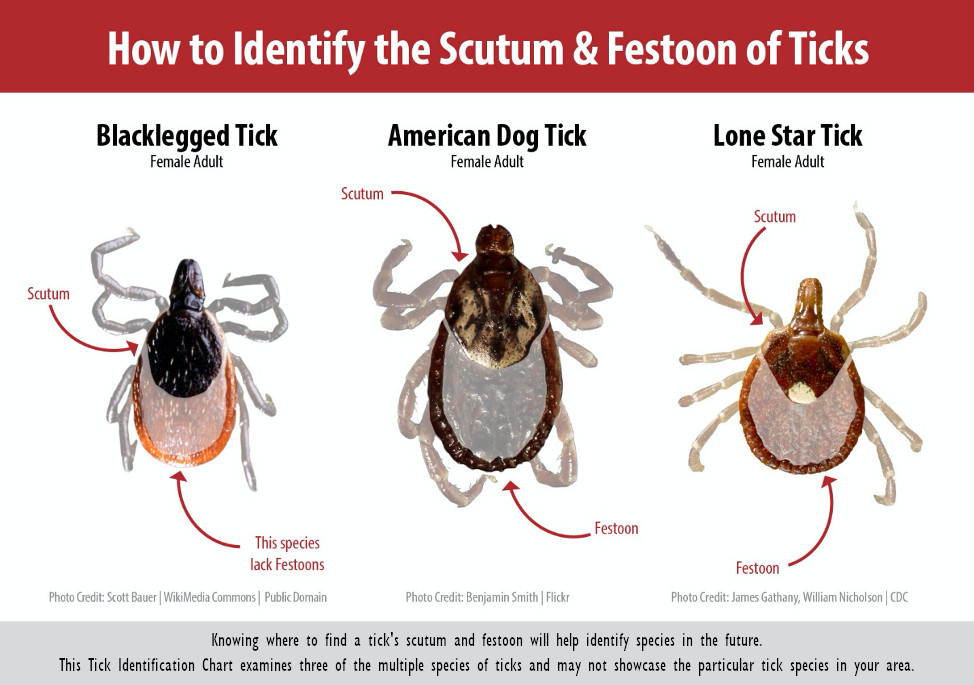

Although it is one of North America’s most common ticks, the Blacklegged (Deer) Tick is hard to spot thanks to its small size (it’s about the same size as a sesame seed). To identify a female Blacklegged (Deer) Tick, look for a reddish-brown body and a black shield on its back. Its mouth parts are long and thin, and there are no festoons present along the abdomen.

Blacklegged Ticks are present throughout the contiguous 48 states and Alaska and thrive in areas with shade and moisture. The greatest risk of being bitten exists in the spring, summer and fall. However, adult ticks may be out searching for a host any time winter temperatures are above freezing. All life stages bite humans, but nymphs and adult females are most commonly found on people.

Photo Credit | Turf Care Supply Corp. | https://www.turfcaresupply.com/blog/2017/06/01/tick-alert

The American Dog Tick (Dermacentor variabilis)

The American Dog Tick makes its home primarily between the East Coast and the Rocky Mountains and prefers wooded, grassy or brushy areas including open pathways in forests and open areas where tree cover is limited. The greatest risk of being bitten occurs during spring and summer.

The biggest of North America’s common ticks, the American Dog Tick is brown with pointed mouth parts and can be distinguished by its decorated dorsal shield. The abdomen also features festoons around its edge.

Research has shown the dog tick to initiate questing behavior in high light intensity environments with low relative humidity. Their questing behavior is similar to the blacklegged tick, as they will typically climb up grass or vegetation and outstretch their legs waiting for an animal to pass by. The American Dog Tick feeds on small animals such as rats and mice in its early stages, but adults are attracted to larger animals. Despite its name, the American Dog Tick is also a threat to humans because of the pathogens it carries. Adult females are most likely to bite humans. This tick can transmit Rocky Mountain spotted fever, Ehrlichiosis and Tularemia to its human hosts, causing serious illness.

Lone Star Tick (Amblyomma americanum)

Until recently, the Lone Star Tick was more commonly found in the southern United States. However, they have spread into northern regions of the country and can be found as far north as Maine. The greatest risk of being bitten exists in early spring through late fall. The Lone Star Tick is commonly found in forested areas and is known to be more aggressive than other species of tick. They will actively seek a host by sensing vibrations and carbon dioxide.

Visually, Lone Star Ticks are easily identifiable due to the trademark white dot found on the dorsal shield of the adult females. Both adult males and females are reddish brown in color, round, and have prominent festoons.

Two of the most common diseases transmitted by Lone Star Ticks are Human Monocytic Ehrlichiosis and Tularemia. Although the Lone Star Tick carries the bacteria that causes Lyme disease, research has shown that it is unable to transmit this disease to a host. The bite of a Lone Star Tick has also been linked to the transmissions of Southern Tick Associated Rash Illness or STARI. The cause of STARI have not been officially determined although it is possible Borrelia lonestari, a genetic relative to Borrelia burgdorferi, is responsible.

Scientists have also confirmed multiple cases in which bites from a Lone Star Tick have resulted in allergic reactions to red meat, known as Alpha-Gal syndrome. This is because the carbohydrate in a lone star tick’s saliva is similar to the structure of a carbohydrate in red meat, so when your immune system creates antibodies to the former, it may simultaneously release them upon interacting with the latter.

A Tick’s Lifecycle

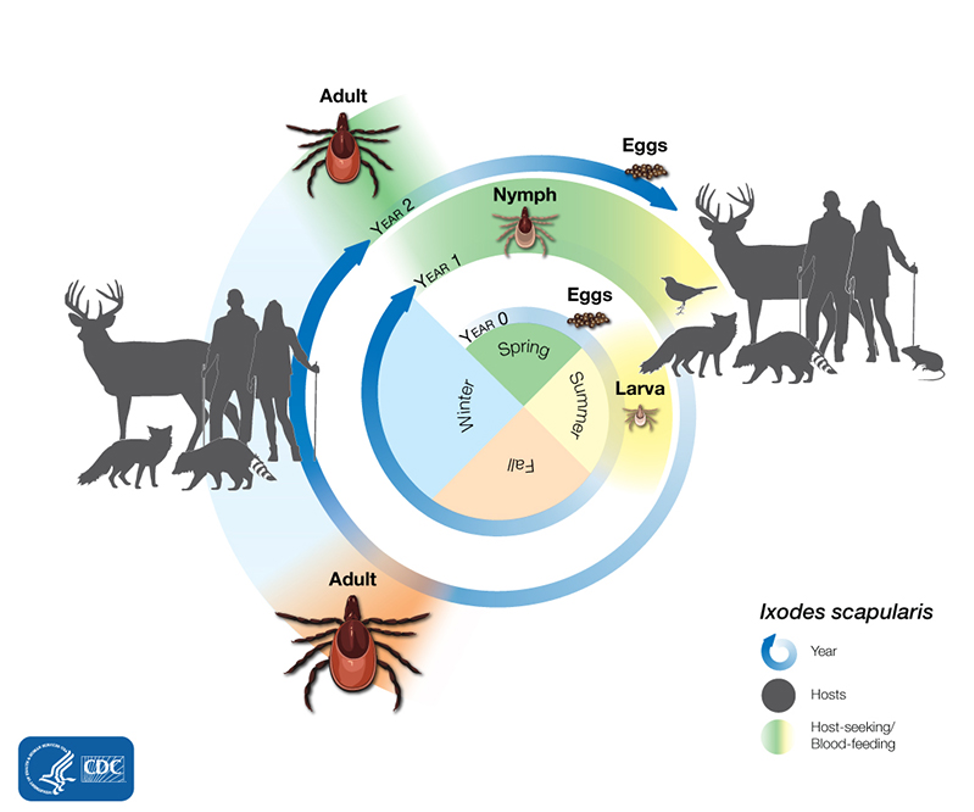

A Blacklegged Tick, for example, can live up to two years where their life generally begins in the spring when adult ticks lay their eggs. In the last weeks of spring or the first weeks of summer, the eggs hatch. Tick larvae feed on birds or other small animals during the summer and then wait out (go dormant) through the winter. During the winter months, the larvae ticks use their blood meal to undergo a transition into their next life stage as a nymph. In the spring, the nymph ticks emerge and begin their quest for a blood meal. Following a blood meal during the nymph life cycle, between spring and fall, they transition or grow into adults where they seek larger hosts such as deer, moose and bears.

Adult ticks are highly active during the fall months, and if they survive the winter, they can emerge during warmer temperatures to seek a host. In the adult life stage, the female tick seeks a full blood meal while the male ticks seek out engorged females to mate. After becoming engorged, the adult female tick will fall off its host, and remain under the leaf litter where she will lay her eggs the following spring season. After laying eggs and mating, the adult ticks will die.

Photo Credit | CDC | https://www.cdc.gov/ticks/life_cycle_and_hosts.html

Tick Myths

There are several misconceptions about ticks. For one, despite the common name Deer (Blacklegged) Tick, deer are not actually capable of spreading Lyme disease. Rather, the white-footed mouse is the reservoir host transmitting Lyme disease to ticks. Additionally, while all tick species may carry Lyme disease, only the Blacklegged Tick can transmit it to a human host.

Finally, the best way to remove a tick is by grasping its head with thin tweezers and pulling straight up away from the skin – contradicting the suggestion that ticks can be removed by burning them, suffocating them with Vaseline or swabbing them with liquid soap. In reality, these methods will only aggravate the tick, which can cause it to release infected saliva into the host.

Learn more about different types of ticks and tick myths at the sources below.

https://www.ticklab.org/tick-identification

https://www.tickipedia.org/tick-myths/